OFLUXO

Keiu Krikmann interviews

Martijn Hendriks

Martijn Hendriks is a Dutch artist who lives and works in Amsterdam. His work explores a wide variety of media and has been exhibited in various galleries worldwide. In this interview, Keiu Krikmann (freelance writer, translator and one of the coordinators of the art space Konstanet), speaks with him about material & immaterial, online circulation and of course, about his process of making art objects within the so-called post-internet age.

Keiu Krikmann: First of all, I’d love to hear about the way you work, the process you go through when making art. In a previous interview you’ve said that even though you’ve increasingly started focusing on material objects, you still might begin with something immaterial, like a text or an image you’ve come across online. How do you manage shifting between the material and immaterial in your work?

KK: Do you think shifting from material to immaterial and vice versa could be seen as an act of translation and if so, how ‘accurate’ do you think these translations between the two realms can even be?

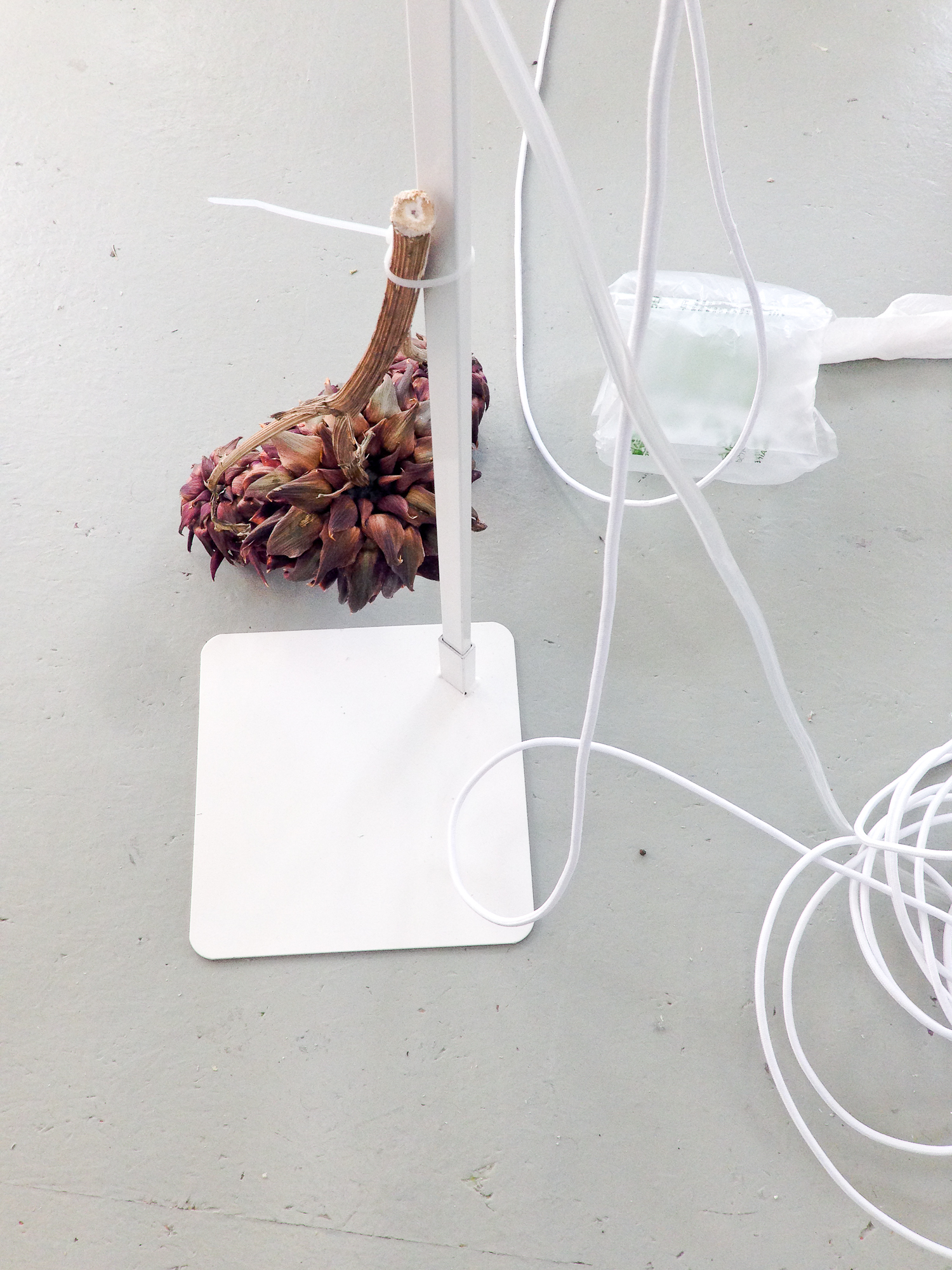

MH: Not accurate at all, probably. But that’s what I like about it. It is a form of translation, but a weird form. Often I feel that material is not like language at all. Sometimes it’s dumb and can’t be read or reinterpreted. So maybe it’s the end point of a message or a press release. Maybe a pop up ad can lead to a sculpture but it won’t send out the same message. But the attempt to use it as a language is what counts. You change the form of something and try to push the idea that this material truly speaks about what it started with. And it does. But it’s a form of translation that continually transforms and contaminates what it translates. As such it is a dysfunctional translation at most, a translation that is closer to the breakdown of functional systems into new and leaky forms than to the idea of a transparent or official use of language.

KK: It seems that contemporary art objects rarely exist just as material objects, as artefacts in their own right, they rather function as representations of an array of immaterial networks. And they eventually seem to exist in a universe of satellites and spin-offs – I mean, depending on the artist, in the process of making art objects, they often produce images that start circulating online, independent from what they were initially related to. Not to mention the same process becomes maybe even more pronounced after the object has been exhibited in a gallery. Do you consider these images that are created in the process of making art objects separate or just alternate versions of the same thing?

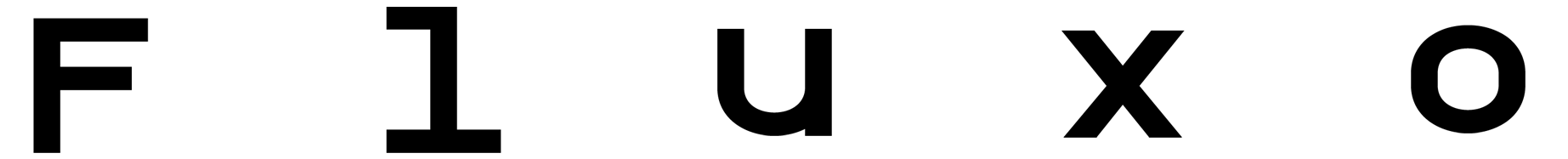

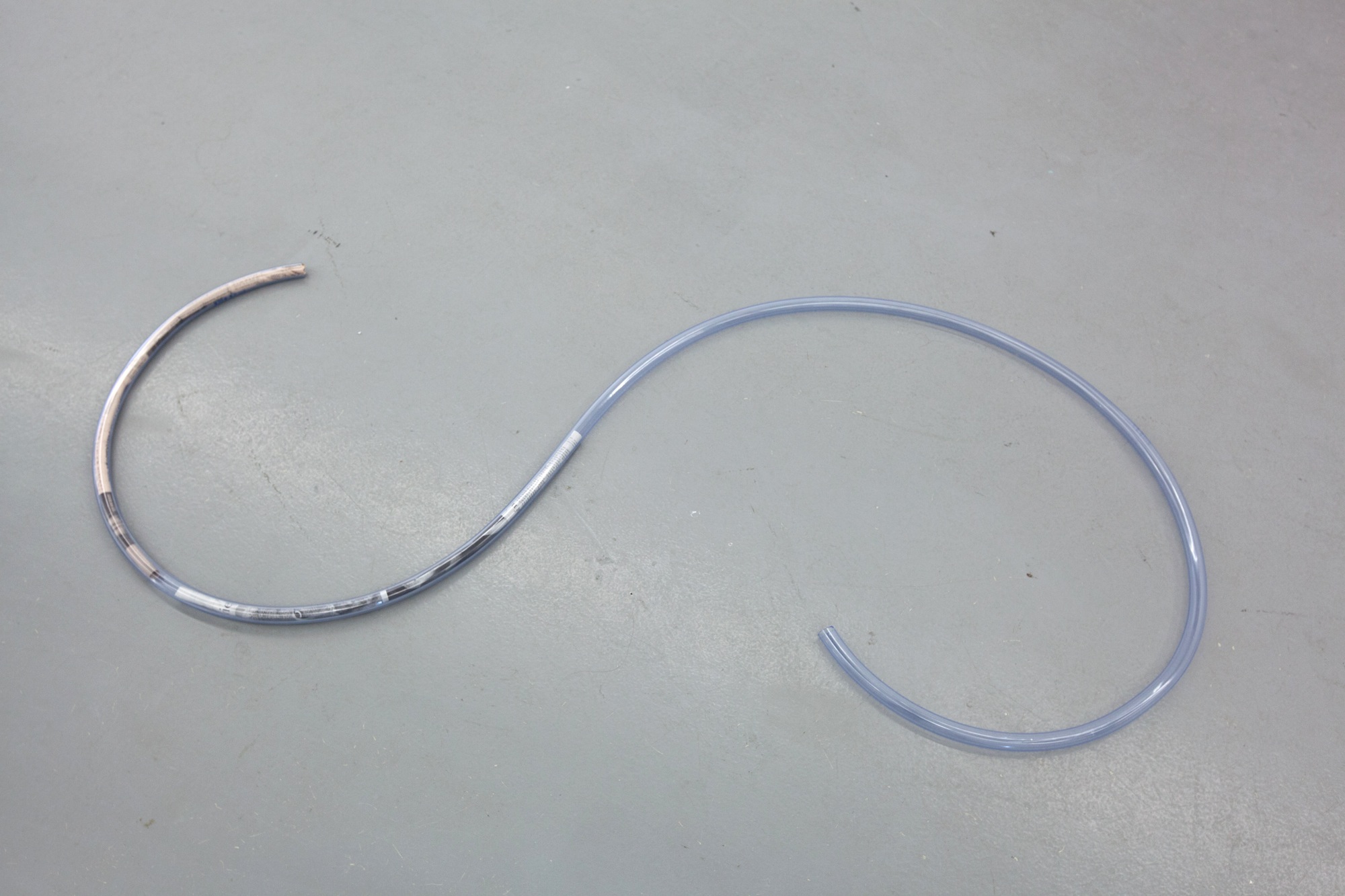

MH: I’m interested in how sculptures are a kind of bodies that enter into and move through different networks – personal, social, technological, financial, material. I like to think of how art works incorporate these networks and how they infect them, dissolve their boundaries, or maybe create their own smaller temporary networks. I think the images that art works generate and which inevitably start circulating faster than the work itself are part of these capabilities. They are a way for a work to enter into other relations than the ones directly available. And the way I see it, it leads to this situation in which one work, like a material sculpture, can lead multiple different but simultaneous lives. Sometimes I approach a sculpture by first doing a photoshop image, but of course they are completely different from physical materials in how messy and unpredictable your process can get. I was working on these strange pieces called Derivatives, a group of wall sculptures that have pieces of clothing drifting in pools of epoxy before hardening into solid shapes, and none of the photoshop sketches I did for them would have told me what happens when you mess up your molds and they start leaking and dripping epoxy resin all over the place, on your shoes, and on the other works. I’ve become interested in feeding this messy, often dysfunctional material process back into a much more immaterial and public daily process, like taking pictures of things I’m working on with my phone, posting them on instagram or tumblr or sometimes on facebook. And somehow the simple act of doing that changes something in how I understand the work I’m doing, as if there is this side to it that makes me feel that generating a form of immaterial circulation through different networks and sharing images of a work with a largely anonymous audience are part of the material process of making a sculpture. I don’t know if this makes sense. It helps me understand my material decisions in a different way, which makes me feel somehow that sculpture is a different thing today than it was before, even in material terms and the forms it takes, because it materializes immaterial processes and their information in different ways. It wants and needs new things.

KK: But in broader terms, the constant shifting between the physical and digital existence has become quite commonplace in our everyday lives. Often without much consideration, we convert our actions into data; our thoughts, feelings and sometimes whole aspects of ourselves are turned into likes and follows. How do you manage that outside your practice, in your daily life – do you embrace it or see this as an inevitability? Is it even possible to log off anymore, and is there a point to it anyway?

MH: I’m just figuring this out as we go. What’s clear is that it’s hardly possible anymore to separate personal and professional life, or what’s private and public. And definitely it has become more complicated to log off, and being unreachable is easily understood as a statement or a socially charged gesture. I don’t know exactly how many times my phone has needed my attention even during this interview but it’s often and it doesn’t stop. It’s not going to become less so it’s better to find a good way of dealing with it. Paradoxically, often it feels like the only viable way to critically and personally deal with it is to over-identify with the accelerating demand to share, to be online, to comment, to self-brand, to like and to follow by embracing it even more than is needed. To over-embrace this situation as a critical strategy. But it definitely makes more sense to me to do this through my work than by putting myself in front of my work. Maybe sculptures and selfies are not so different when it comes to online circulation.

KK: Alongside these transformations, the meaning of the word ‘labour’ has also changed, it has been extended to new spheres – we now talk about immaterial labour, affective labour, digital labour etc. What do you think ‘labour’ means to artists working within the so-called post-internet condition?

MH: I don’t know about this. I try not to think of the question of labour too much when I’m working. I enjoyed reading people like Maurizio Lazzarato, Franco “Bifo” Berardi or John Kelsey, though. Berardi’s The Soul at Work and Kelsey’s text for Artforum called Next-Level Spleen were important in how we could think about the relationship between work and art at some point. It’s interesting that at this moment discussions of networked life often bring up issues of panic, crisis, network-fatigue, network-disgust, exhaustion, and so on. Part of that mix is the feeling that many artists I know go through, this sense that their online social life is as important to their practice and productivity as having a studio. Maybe it is. It’s interesting to see, also, how the term post-internet seems to have completely deflated in a very short time span. For a short moment it seemed to have an edge, it seemed to bring together a group of artists that was internationally dispersed but brought together by shared interests. Right now it feels as if the spread and use of the internet has become such a banal and everyday fact of life that it doesn’t need to be pointed out so much anymore in these very large historical terms. I think that’s a good thing, because it creates a need to articulate your work in more individual and particular terms. Now that the novelty of making work that shows its awareness of networked life has worn off, we can get to the good stuff. For me this brings up the notion that networks are not just there to be used or celebrated but can also be charted as they mutate into different forms, dissolve into other networks, disintegrate, or introduce disruptive moments into previously balanced situations.

KK: And even though everything appears to become increasingly dematerialised, you still work with actual, real life materials. So, what does it mean to work with material, to make sculptures – why do you think there’s still a keen interest in materiality?

MH: For me this choice is motivated exactly by this doubleness, by the strange status and possibilities of material sculpture in times of immaterial labor. The ways that we relate to the material world are changing rapidly and working with materiality allows me to register and respond to that. What interests me is a kind of insistent physicality of experience: no matter how entangled we become with the immaterial world of digital networks, finance and technology, these transformations express themselves ultimately through physical, material reality. The messier and more hybrid this reality gets, the more it interests me as a sculptor. There are many great artists working in sculpture at the moment and I think the issue of materiality in the contemporary context is an issue that underlies some very diverse sculptural practices that I am excited about.

KK: Also, what does it mean to present these material objects in a gallery – I asked you about the universe created in the process of making art objects – do you see the sculptures as a kind of a crystallisation that just happens at some point or are they more like the pinnacle, like the ultimate expression of that process?

MH: That’s a good question. I really have to force myself to stop working on certain sculptures. Often I typically still consider adding elements or changing things very far in the process of installing a show. And then the process doesn’t stop. Whenever I have to leave a work alone and tell myself that it works in that form, I often continue with the process that led to that form. In a way I think of material sculptures as part of the script I’m working with, just translated into material forms, and both are somehow pretty much fluid, with forms I work with always mutating into other forms.

KK: I also know that you’ve got a show coming up – you’re participating in a large group exhibition next year and you’ve began working on some new things. Would you mind talking about these works a little; how do they relate to your practice and if you’ve maybe started exploring any new themes?

MH: It’s always tricky to talk about new work that’s still developing but I can try and say a few things. If you take the two main topics we talked about, materiality and immateriality, and how they continuously infect each other, I think that the new work comes from a desire to radicalize the hybrid relation between them. One theme that’s developing in my work at the moment is the changing idea of anthropomorphism, the human subject and body seemingly falling apart and at the same time being held together by their entanglement with socio-technological networks, motivational language, commercialized care of the self, finance and debt structures. I’m collecting texts on the internet that talk about these issues and I’m turning them into a new script. The kind of materiality I’m looking into for these new works is more outspoken in its embrace of the possibility of contamination. For example, fluids that turn solid, liquids, UV and inkjet prints on adhesive materials, but also bringing in the possibility of working with elements that generate warmth, light and movement, as ways of shaking up the presumed stability of material objects. I’m really excited about these new works.

Martijn Hendriks

Interview by Keiu Krikmann, a freelance writer, translator and one of the coordinators of Konstanet.

O Fluxo, October 2014

OFLUXO is proudly powered by WordPress