OFLUXO

An Open Net Casts Shadows

Hannah Mitterwallner, Lukas Hoffmann, Johanna Kunze, Ivo Rick

At Kunstbunker Nuernberg

October 22 — November 27, 2022

When I read a Thousand Plateaus [1], I like to first focus on Deleuze and Guattari’s more tangible examples – Prof. Challenger (the hot-headed, misogynistic character of Conan Doyle novels) [2], lobsters (with two pincers) or even the judgement of God – in the somewhat misguided hope that these might help when following their difficult and often convoluted arguments. Alas, these examples are often not as tangible as they might seem: Virginia Woolf’s schools of fish for instance. Derek Ryan cops out outright. He claims it is beyond the scope of his chapter to expand upon the relations between Woolf and monkeys or fish [3]. Instead he offers a link to Kathryn Simpson’s essay, ‘Queer Fish’ [4], which is less than helpful as the topic here is not fish but mermaids. Elusive fish aside, my interest here lies in ‘nets’. These bear a relation to Woolf’s fish, but have more to do with epistemology. In the much earlier Difference and Repetition Deleuze describes Kant’s conditions of the possibility of experience as a net which is so ‘loose’ that ‘the largest fish pass through’ [5]. What he means in his critique of representation, is that these conditions, pre-existing and pre-defined, universal, abstract and remote, cannot capture the real nature of our surrounding world.

Nevertheless, in epistemology this capture of the world is at stake. We want to understand – we want to know how we understand – our given reality. So we throw the proverbial net. It is interesting, this net, which hovers briefly still in the air, before gently settling on some patch unknown. We do not know where it will land or what it might catch. The reference here is to Louis Hjelmslev and his theory of language [6]. Unlike other linguists, Hjelmslev has a much broader understanding of signification, beyond the signifier and signified, encompassing the notions of matter, content and expression, form and substance – with both content and expression having form and matter. These together weave a complex net of double articulation; the net falls on what for Hjelmslev is common to all languages, ‘mening’ in Danish, described as ‘an amorphous thought mass’. For Deleuze and Guattari this is the plane of consistency, ‘the unformed, unorganized, nonstratified, or destratified body and all its flows: subatomic and submolecular particles, pure intensities, prevital and prephysical free singularities.’ [7] The point is, that first articulation of content, the brief glimpse of shadow before the net falls, is not only unconscious but inorganic, even molecular. Deleuze and Guattari discuss linguistics in combination with genetics and protein building. The second reference is to Jacques Monod, who in his essay ‘Chance and Necessity’ shows that organised life is the result of certain blind processes [8]. In the first instance, selection and coding (which then leads onwards to overcoming and integration) occurs mechanically, for Deleuze and Guattari much like the process of aggregation forming the stratum in geology. A cell selects when the protein enzyme acts on its one substrate. It acts or it does not. But whether or not it acts is determined by a complex regulatory circuit of biochemical interactions between a repressor protein, the gene for the enzyme, and the substrate of the enzyme. So ultimately it is the enzyme’s chemical environment that determines its activity and not some rational decision on the cell’s part. That first selection process – the one lobster pincer – occurs without the cell’s active involvement, its ability to choose at the level of metabolic activity being generated by the choiceness interaction at another, arising from a complicated system of feedback loops.

The earth in this linguistic, biochemical context is alive, but this does not mean it is Professor Challenger’s earth, a giant sea urchin that requires a giant prick to penetrate and prove its existence [9]. Rather, it means that earth resides in us. Every time we think and speak, it is because of a mechanical process that is taking place without our knowledge, in relation to the conditions posed by our current environment.

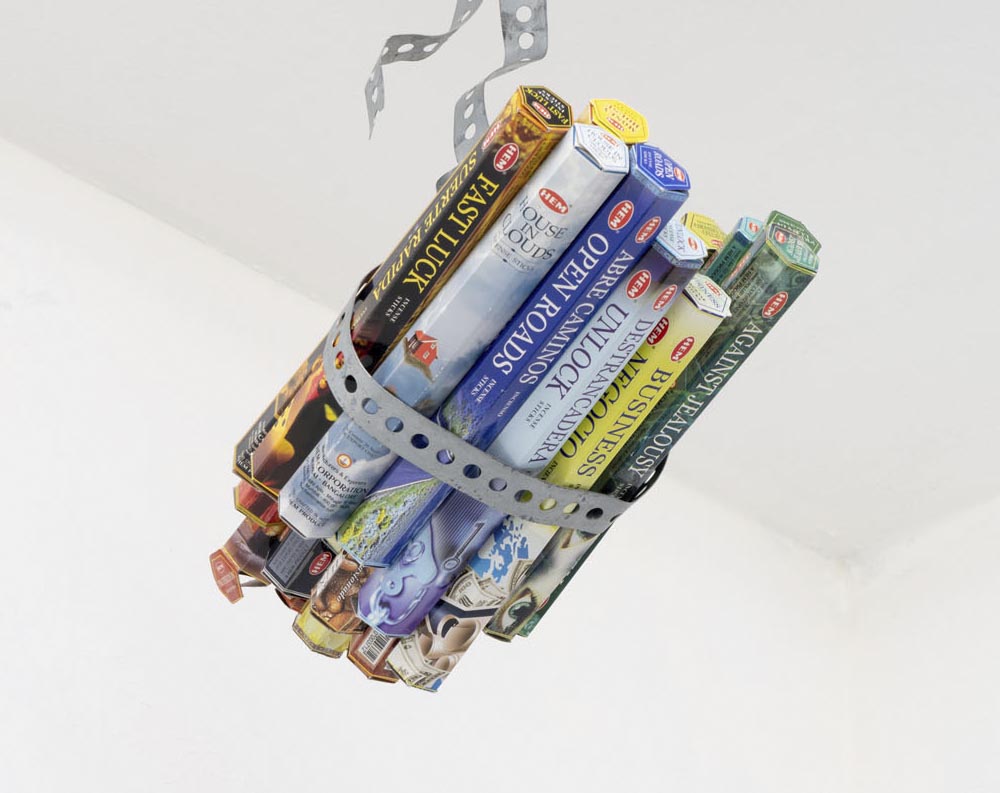

All the artists in this exhibition work with sculpture, making objects that seem to stem from a world of science fiction. Strange structures propagate, some resembling natural structures – trees, mushrooms, oceans – but from a distant world or planet; many are much more artificial. I see work that gives the impression of being technologically advanced, like Ivo Rick’s technoid fossils of hiking boots or Lukas Hoffman’s fishing rods (to better catch Virginia Woolf’s fish!), yet other pieces look far more low tech, almost primitive. Hannah Mitterwallner grows delicate branches out of sugar and fashions cages to hang from them, like a shaman hanging protective talismans in an obscure ritual. Similarly to Conan Doyle stories, in this world where magic abounds, the earth lives. It may not scream when penetrated, but it weeps crystal-like beads in the sculptures of Johanna Kunze, which seem to form and reform in front of our eyes. This is not an earth personified and humanised, but an earth aware of its molecular geology. Whereas landscape is organised, like Mitterwallner’s white blocks arranged grid-like on the floor or the 3D grid structure of Lukas Hoffmann’s wave, this earth is not. It aggregates, leaving lines of sediment behind, those delicately drawn by Kunze on her surfaces, or more physically, in Rick’s use of clay. It rejoices in the mechanic: again, in his work Rick uses algorithms of fixed points and forces to produce support structures for his teeth or clay feet.

In this work, there are references to signification, especially in the way we are invited to place utensils into Mitterwallner’s empty bodies, as if willing to understand them in the most childlike of ways. There are also many references to biological processes: weeping, sweating, growing, developing, decaying. But what I find is most pervasive, linking all these various pieces, is the sense of the inorganic and mechanical bubbling underneath the often glossy finish of the objects, a thin veneer solidifying on an amorphous mass. A net is set, a tight net, its mesh the size of molecules, and flung out to sea.

[1] Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix, Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi, Minneapolis, London: University of Minesota Press 2005.[2] See especially Conan Doyle, Arthur, ‘When the world screamed’, 1928, https://www.globalgreyebooks.com/when-the-world-screamed-ebook.html[3] Ryan, Derek, Virginia Woolf and the Materiality of Theory: Sex, Animal, Life, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 2013.[4] Simpson, Kathryn, ‘Queer Fish”: Woolf’s Writing of Desire Between Women in “The Voyage Out” and “Mrs Dalloway’ in Woolf Studies Annual, Vol. 9, SPECIAL ISSUE: Virginia Woolf and Literary History: Part I, 2003, pp. 55-82.)[5] Deleuze, Gilles, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton, New York: Continuum, 2001, p. 68.[6] Thousand Plateaus, pp. 43-5.[7] Ibid. p. 43.[8] Ibid. p. 49.[9] Doyle ‘When the world screamed’.

— Magdalena Wisniowska

Previous Articles

OFLUXO is proudly powered by WordPress