True Lies

by Timur Si-Qin

Form is emptiness; emptiness is form.

Emptiness is not separate from form; form is not separate from emptiness.

Whatever is form is emptiness; whatever is emptiness is form.

– Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra

What motivates my work is a type of secularism – one born not from apathy or the lack of wonder about the world, but rather from the belief that existence itself, a seemingly improbable state, is divine and therefore does not need to be devalued by a belief in things that do not exist.

An unexamined belief in labels and essences can lead to myriad problems. Today, race and gender essentialism can be blamed for the misunderstandings that lead to racism and sexism. To a racist, race is an immutable quality that concretely defines one’s identity; to a sexist, gender is an immutable reality with a set of essential qualities. However, in reality, race and gender are temporally specific, porous accumulations of characteristics and behaviors. Contrary to popular misconceptions about evolutionary theory’s link to racism, it was Darwin who first broke Western thought free from the long-held understanding of race as a real thing.

As philosopher Manuel De Landa tells us: “When the ideas of Darwin on the role of natural selection and those of Mendel on the dynamics of genetic inheritance were brought together six decades ago, the domination of the Aristotelian paradigm came to an end. It became clear, for instance, that there was no such thing as a preexistent collection of traits defining ‘zebrahood’. Each of the particular adaptive traits […] (camouflage, running speed and so on) happened to come together in zebras.” And yet, as De Landa writes, “they may not have, had the actual history of those populations been any different. In short, for population thinkers, only the variation is real, and the ideal type (e.g. the average zebra) is a mere shadow.” 1

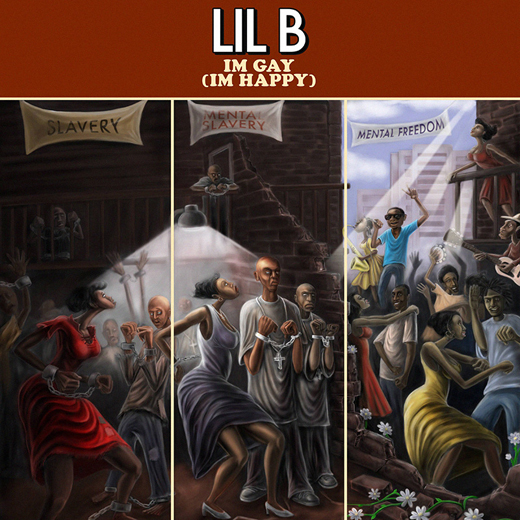

Just as there is nothing eternal and transcendent that the word “zebra” references, there is nothing transcendent or eternal about the meaning of any word. The Bay-area rapper Lil B, “The Based-God,” implicitly understood the lack of essential connections between signs and referents when he decided to name his 2011 album “I’m Gay.” Combining meanings and using words in seemingly random ways to serve abstract compositional functions, he is known for pioneering a strain of hip-hop that entirely exploited the modular capacity of language. Inferring from his music, one can assume that Lil B’s decision to name his album “I’m Gay” was not to come out as homosexual, or to make any statement on sexuality whatsoever. Instead it was motivated by the understanding that words are not inherently imbued with meaning, and therefore that they can be recoded and misused. Unfortunately, Lil B, following the announcement of “I’m Gay,” received harsh, homophobic criticism and backed down from the true deterritorializing potential of the album’s name, giving it the subtitle “I’m Happy” (referencing the older usage of “gay”) and thereby conceding to hate and the established sign-referent connection driving it.

But long before Darwin and Lil B, a rejection of essences was formulated by the ancient eastern philosophies of the Buddhists and Taoists: “[V]oidness does not mean nothingness, but rather that all things lack intrinsic reality, intrinsic objectivity, intrinsic identity or intrinsic referentiality. Lacking such static essence or substance does not make them not exist – it makes them thoroughly relative.” 2

And even more to the point:

“The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the eternal Name. The unnamable is the eternally real.” 3

Eastern philosophies teach that the knowledge and acceptance of the true nature of reality (as being dynamic, contingent, and without eternal essence) is necessary for attaining true freedom. The permanent identity of anything at all is an illusion – including the structures that constrain our lives and thoughts. Buddhists and Taoists longago understood that life is inherently open-ended.

Applied to art and photography, one can see how asking about the “core operations” of a given medium is no more meaningful than asking about the core traits of zebras. Ultimately there is no such thing as a fixed or stable identity, whether of signifiers or otherwise. The “index” of photography is a historical accumulation of processes and technologies based on a simulation of the human eye – but one that, like the eye itself, is not limited to this originating design (see exaptation, the adaptation of a trait that diverges from its originating function). Even something like infrared spectrum photography is an instance of the camera having developed beyond the human eye, and today digital photography is evolving functions completely abstract to it – sticker overlays or regram screenshots, for example.

A rejection of essences also leads to a rejection of an overtly etymological approach to creating and understanding art. Just because a given word had a different meaning in Greek, doesn’t mean that this original meaning is somehow stil homeopathically latent in the word. True creative freedom comes in recognizing that there is nothing inherently masculine about cold, minimalist metal sculptures or inherently feminine about delicate pastel performance art. In fact there is nothing inherently “masculine” about males or “feminine” about females.

My own work is largely animated by this rejection of essences. Part of the reason I use commercial photography – specifically the kind that is currently standard for the advertising of mass consumer goods – as a material lies in my interest in loosening the structural power of associations. Images are often falsely interpreted and essentialized as being expressions of things such as “capitalism” (which arguably is itself only a reified signifier of incongruous, heterogenous processes). Essentializing the “race” of images leads some to reject and fear certain kinds of images. In art this essentialization and rejection oftentimes expresses itself in a preference for old or nostalgic materials, because the image world of the present is prejudged to be sinful and dangerous. I’ve always felt this misconception gives too much power to images whose properties and capacities can be retooled to the core due to their lack of inherent identity. By using the sign stripped of its referent, one loosens the structural power of associations. This sign-referent destabilization can have a deterritorializing effect necessitating the creation of new meanings.

“What makes simulation interesting is the fact that there is something that can be simulated, to varying degrees of accuracy, in the first place, meaning all simulations, no matter how good or bad, exist within a relation to the real.”

If this spiritually motivated secularism rejects essentialism on the one hand, it nevertheless affirms the existence of the immanent and real on the other. Expressing itself in a realist/materialist philosophical commitment, this kind of secularism accepts that there exists a mind-independent reality outside of, before, and after one’s phenomenological experience. In art criticism, realism/ materialism today is popularly misunderstood as a reductionist, overtly rational approach to understanding the world, one not sensitive to the delicate and irrational embers necessary for artworks to be born. However realism/materialism does not reject the reality of the phenomenal, but rather seeks to put it in context. In Levi Bryant’s words:

“… What is at stake in the New Materialisms and some of the Speculative Realisms […] is not some hackneyed attempt to champion the sciences and objectivity over meaning, but to draw attention to the material dimensions of how we dwell and live. […] Materiality is not phenomenality, a lived experience, a meaning, nor a text – though it can affect all of these things – but something with its own dynamics and forms of power. We need a form of theory capable of thinking that and that avoids the urge to treat everything as texts, meanings, and correlates of intentions.” 4

So then the interesting question becomes: what is real about a photograph today, especially if it can be digitally constructed and Photoshopped? In its 2005 catalog, Ikea included a 3-D rendering of a small wooden chair. It was the result of a yearlong project by three graphic design interns. The inclusion tested whether or not any customers would notice that the object was not real: presumably, they did not as, since then, the amount of 3-D rendered objects depicted in Ikea’s catalogs has risen to 12% in 2012, 25% in 2013, and up to 75% in 2014. 5

This rapid shift from photographing sets to rendering them was driven by economics. Because Ikea customizes its catalogs to cater to the tastes of different geographic regions, it produces many variations of, say, a kitchen, featuring dark woods for one and light woods for another. Now that these kinds of small changes can be made instantaneously on-screen – technologies such as ray-tracing, for example, allow the creation of digital images that are now effectively indistinguishable from traditional photography – production costs can be significantly reduced.

With these advancements, the first conclusion one arrives at is that the photograph is no longer a document of reality as such, which may be true in varying contexts. However, the effectiveness of photography and simulated images provide evidence of a deeper philosophical insight – namely the existence of the real of perception. The reason Ikea catalogs can convince people that the products depicted are real is because there is a real way that humans perceive the world around them – which can then be simulated, even if only by approximation.

What makes simulation interesting is the fact that there is something that can be simulated, to varying degrees of accuracy, in the first place, meaning all simulations, no matter how good or bad, exist within a relation to the real. Or as De Landa would say, the possibility space of simulated images provides an overlap with the possibility space of perception. 6

The reason that the most effective advertising appears/operates as it does is owed to the fact that commercial interests are incentivized to adopt a realist model of the world; to optimize their message in correspondence with the perceptions of their target consumers. Psychological research on perception pays off for commercial interests who vastly outcompete the fine arts for attention and resources. This is not to say that the fine arts should try to compete with the commercial image or do anything different than what it already does. After all, art, in its most idealized form, is already an exploration of the possibility fields of the world. Not only does a belief in the real open paths of investigation – as does the philosophical basis of science – but the use of that knowledge can disarm images, offering the potential to construct new images with new properties and new capacities.

[1] Manuel De Landa, Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy, London 2002.

[2] From the preface of Lex Hixon, Mother of the Buddhas, Wheaton, IL 1993.

[3] Lao Zi, Tao Te Ching (trans. by Stephen Mitchell), New York 1998.

[4] Levi Bryant, in a blogpost posted February 2, 2015, https://larvalsubjects.wordpress.com/2015/02/10/critical-reflections-on-the-humanities-and-social-sciences/.

[5] See: Kirsty Parken, “Building 3D with Ikea”, posted June 25, 2014, http://www.cgsociety.org/index.php/CGSFeatures/CGSFeatureSpecial/building_3d_with_ikea.

[6] De Landa, op. cit.

Written by Timur Si-Qin,

2018